Two truths doctrine Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Two_truths_doctrine

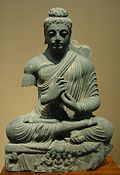

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

The Buddhist doctrine of the two truths (Sanskrit: dvasatya, Wylie: bden pa gnyis) differentiates between two levels of satya (Sanskrit; Pāli: sacca; meaning "truth" or "reality") in the teaching of Śākyamuni Buddha: the "conventional" or "provisional" (saṁvṛti) truth, and the "absolute" or "ultimate" (paramārtha) truth.[1][2]

The exact meaning varies between the various Buddhist schools and traditions. The best known interpretation is from the Mādhyamaka school of Mahāyāna Buddhism, whose founder was the 3rd-century Indian Buddhist monk and philosopher Nāgārjuna.[1] For Nāgārjuna, the two truths are epistemological truths.[2] The phenomenal world is accorded a provisional existence.[2] The character of the phenomenal world is declared to be neither real nor unreal, but logically indeterminable.[2] Ultimately, all phenomena are empty (śūnyatā) of an inherent self or essence due to the non-existence of the self (anātman),[3] but temporarily exist depending on other phenomena (pratītya-samutpāda).[1][2]

In Chinese Buddhism, the Mādhyamaka thought is accepted, and the two truths doctrine is understood as referring to two ontological truths. Reality exists in two levels, a relative level and an absolute level.[4] Based on their understanding of the Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra, the Chinese Buddhist monks and philosophers supposed that the teaching of the Buddha-nature (tathāgatagarbha) was, as stated by that Sūtra, the final Buddhist teaching, and that there is an essential truth above emptiness (śūnyatā) and the two truths.[5]

The doctrine of emptiness (śūnyatā) is an attempt to show that it is neither proper nor strictly justifiable to regard any metaphysical system as absolutely valid. The two truths doctrine doesn't lead to the extreme philosophical views of eternalism (or absolutism) and annihilationism (or nihilism), but strikes a middle course (madhyamāpratipada) between them.[1]

Etymology and meaning

[edit]Satya is usually taken to mean "truth", but also refers to "a reality", "a genuinely real existent".[6] Satya (Sat-yá)[7] is derived from Sat and ya. Sat means being, reality, and is the present participle of the root as, "to be" (Proto-Indo-European *h₁es-; cognate to English is).[7] Ya and yam means "advancing, supporting, hold up, sustain, one that moves".[8][9] As a composite word, Satya and Satyam imply that "which supports, sustains and advances reality, being"; it literally means, "that which is true, actual, real, genuine, trustworthy, valid".[7]

The two truths doctrine states that there is:

- Provisional or conventional truth (Sanskrit saṁvṛti-satya, Pāli sammuti sacca, Tibetan kun-rdzob bden-pa), which describes our daily experience of a concrete world, and

- Ultimate truth (Sanskrit paramārtha-satya, Pāli paramattha sacca, Tibetan: don-dam bden-pa), which describes the ultimate reality as śūnyatā, empty of concrete and inherent characteristics.

The 7th-century Buddhist philosopher Chandrakīrti suggests three possible meanings of saṁvṛti: [1]

- complete covering or the "screen" of ignorance which hides truth;

- existence or origination through dependence, mutual conditioning;

- worldly behavior or speech behavior involving designation and designatum, cognition and cognitum.

The conventional truth may be interpreted as "obscurative truth" or "that which obscures the true nature" as a result. It is constituted by the appearances of mistaken awareness. Conventional truth would be the appearance that includes a duality of apprehender and apprehended, and objects perceived within that. Ultimate truths are phenomena free from the duality of apprehender and apprehended.[10]

Background

[edit]The teaching of Śākyamuni Buddha may be viewed as an eightfold path (mārga) of release from the causes of suffering (duḥkha). The First Noble Truth equates life-experiences with pain and suffering. The Buddha's language was simple and colloquial. Naturally, various statements of the Buddha at times appear contradictory to each other. Later Buddhist teachers were faced with the problem of resolving these contradictions.

The 3rd-century Indian Buddhist monk and philosopher Nāgārjuna and other Buddhist philosophers after him introduced an exegetical technique of distinguishing between two levels of truth, the conventional and the ultimate.[1]

A similar method is reflected in the Brahmanical exegesis of the Vedic scriptures, which combine the ritualistic injunctions of the Brahmanas and speculative philosophical questions of the Upanishads as one whole "revealed" body of work, thereby contrasting the jñāna kāņḍa with karmakāņḍa.[1]

Origin and development

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Buddhist philosophy |

|---|

|

|

|

The concept of the two truths is associated with the Mādhyamaka school of Mahāyāna Buddhism, whose founder was the 3rd-century Indian Buddhist monk and philosopher Nāgārjuna,[1][11] and its history traced back to the earliest years of Buddhism.

Early Indian Buddhism

[edit]Theravāda

[edit]In the Pāli Canon, the distinction is not made between a lower truth and a higher truth, but rather between two kinds of expressions of the same truth, which must be interpreted differently. Thus a phrase or passage, or a whole Sūtra, might be classified as neyyattha, samuti, or vohāra, but it is not regarded at this stage as expressing or conveying a different level of truth.

Nītattha (Pāli; Sanskrit: nītārtha), "of plain or clear meaning"[12] and neyyattha (Pāli; Sanskrit: neyartha), "[a word or sentence] having a sense that can only be guessed".[12] These terms were used to identify texts or statements that either did or did not require additional interpretation. A nītattha text required no explanation, while a neyyattha one might mislead some people unless properly explained:[13]

There are these two who misrepresent the Tathāgata. Which two? He who represents a Sutta of indirect meaning as a Sutta of direct meaning and he who represents a Sutta of direct meaning as a Sutta of indirect meaning.[14]

Saṃmuti or samuti (Pāli; Sanskrit: saṃvṛti), meaning "common consent, general opinion, convention",[15] and paramattha (Pāli; Sanskrit: paramārtha), meaning "ultimate", are used to distinguish conventional or common-sense language, as used in metaphors or for the sake of convenience, from language used to express higher truths directly. The term vohāra (Pāli; Sanskrit: vyavahāra, "common practice, convention, custom" is also used in more or less the same sense as samuti.

The Theravādin commentators expanded on these categories and began applying them not only to expressions but to the truth then expressed:

The Awakened One, the best of teachers, spoke of two truths, conventional and higher; no third is ascertained; a conventional statement is true because of convention and a higher statement is true as disclosing the true characteristics of events.[16]

Prajnāptivāda

[edit]The Prajñaptivāda school took up the distinction between the conventional (saṃvṛti) and ultimate (paramārtha) truths, and extended the concept to metaphysical-phenomenological constituents (dharma), distinguishing those that are real (tattva) from those that are purely conceptual, i.e., ultimately nonexistent (prajñāpti).

Indian Mahāyāna Buddhism

[edit]

Mādhyamaka school

[edit]The distinction between the two truths (satyadvayavibhāga) was fully developed by Nāgārjuna (c. 150 – c. 250 CE), founder of the Mādhyamaka school of Buddhist philosophy.[1][11] Mādhyamika philosophers distinguish between saṃvṛti-satya, "empirical truth",[17] "relative truth",[web 1] "truth that keeps the ultimate truth concealed",[18] and paramārtha-satya, ultimate truth.[19][web 1]

Saṃvṛti-satya can be further divided in tathya-saṃvṛti or loka-saṃvṛti, and mithya-saṃvṛti or aloka-saṃvṛti,[20][21][22][23] "true saṃvṛti" and "false saṃvṛti".[23][web 1][note 1] Tathya-saṃvṛti or "true saṃvṛti" refers to "things" which concretely exist and can be perceived as such by the senses, while mithya-saṃvṛti or "false saṃvṛti" refers to false cognitions of "things" which do not exist as they are perceived.[22][23][18][note 2][note 3]

Nāgārjuna's Mūlamadhyamakakārikā provides a logical defense for the claim that all things are empty (śūnyatā) and devoid of any inherently-existing self-nature (anātman).[11] Emptiness itself, however, is also shown to be "empty", and Nāgārjuna's assertion of "the emptiness of emptiness" prevents the mistake of believing that emptiness may constitute a higher or ultimate reality.[28][29][note 4][note 5] Nāgārjuna's view is that "the ultimate truth is that there is no ultimate truth".[29] According to Siderits, Nāgārjuna is a "semantic anti-dualist" who posits that there are only conventional truths.[29] Jay L. Garfield explains:

Suppose that we take a conventional entity, such as a table. We analyze it to demonstrate its emptiness, finding that there is no table apart from its parts [...] So we conclude that it is empty. But now let us analyze that emptiness […]. What do we find? Nothing at all but the table’s lack of inherent existence [...] To see the table as empty [...] is to see the table as conventional, as dependent.[28]

In Nāgārjuna's Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, the two truths doctrine is used to defend the identification of dependent origination (pratītya-samutpāda) with emptiness itself (śūnyatā):

The Buddha's teaching of the Dharma is based on two truths: a truth of worldly convention and an ultimate truth. Those who do not understand the distinction drawn between these two truths do not understand the Buddha's profound truth. Without a foundation in the conventional truth the significance of the ultimate cannot be taught. Without understanding the significance of the ultimate, liberation is not achieved.[31]

In Nāgārjuna's own words:

8. The teaching by the Buddhas of the Dharma has recourse to two truths:

The world-ensconced truth and the truth which is the highest sense.

9. Those who do not know the distribution (vibhagam) of the two kinds of truth

Do not know the profound "point" (tattva) in the teaching of the Buddha.

10. The highest sense of the truth is not taught apart from practical behavior,

And without having understood the highest sense one cannot understand nirvana.[32]

Nāgārjuna based his statement of the two truths on the Kaccāyanagotta Sutta. In this text, Śākyamuni Buddha, speaking to the monk Kaccāyana Gotta on the topic of right view, describes the middle course (madhyamāpratipada) between the extreme philosophical views of eternalism (or absolutism) and annihilationism (or nihilism):

By and large, Kaccāyana, this world is supported by a polarity, that of existence and non-existence. But when one sees the origination of the world as it actually is with right discernment, "non-existence" with reference to the world does not occur to one. When one sees the cessation of the world as it actually is with right discernment, "existence" with reference to the world does not occur to one.[33]

According to the Tibetologist Alaka Majumder Chattopadhyaya, although Nāgārjuna presents his understanding of the two truths as a clarification of the teachings of the historical Buddha, the two truths doctrine as such is not part of the earliest Buddhist tradition.[34]

Buddhist Idealism

[edit]Yogācāra

[edit]The Yogācāra school of Buddhist philosophy distinguishes the Three Natures and the Trikāya. The Three Natures are:[35][36]

- Paramarthika (transcendental reality), also referred to as Parinispanna in Yogācāra literature: The level of a storehouse of consciousness that is responsible for the appearance of the world of external objects. It is the only ultimate reality.

- Paratantrika (dependent or empirical reality): The level of the empirical world experienced in ordinary life. For example, the snake-seen-in-the-snake.

- Parikalpita (imaginary). For example, the snake-seen-in-a-dream.

Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra

[edit]The Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, one of the earliest Mahāyāna Sūtras, took an idealistic turn in apprehending reality. Japanese Buddhist scholar D. T. Suzuki writes the following explanation:

The Laṅkā is quite explicit in assuming two forms of knowledge: the one for grasping the absolute or entering into the realm of Mind-only, and the other for understanding existence in its dual aspect in which logic prevails and the vijñānas are active. The latter is designated discrimination (vikalpa) in the Laṅkā and the former transcendental wisdom or knowledge (prajñā). To distinguish these two forms of knowledge is most essential in Buddhist philosophy.

East Asian Buddhism

[edit]When Buddhism was introduced to China by Buddhist monks from the Indo-Greek Kingdom of Gandhāra (now Afghanistan) and classical India between the 2nd century BCE and 1st century CE, the two truths teaching was initially understood and interpreted through various ideas in Chinese philosophy, including Confucian[37] and Taoist[38][39][40] ideas which influenced the vocabulary of Chinese Buddhism.[41] As such, Chinese translations of Buddhist texts and philosophical treatises made use of native Chinese terminology, such as "T’i -yung" (體用, "Essence and Function") and "Li-Shih" (理事, Noumenon and Phenomenon) to refer to the two truths. These concepts were later developed in several East Asian Buddhist traditions, such as the Wéishí and Huayan schools.[41] The doctrines of these schools also influenced the ideas of Chán (Zen) Buddhism, as can be seen in the Verses of the Five Ranks of Tōzan and other Chinese Buddhist texts.[42]

Chinese thinkers often took the two truths to refer to two ontological truths (two ways of being, or levels of existence): a relative level and an absolute level.[4] For example, Taoists at first misunderstood emptiness (śūnyatā) to be akin to the Taoist notion of non-being.[43] In the Mādhyamaka school of Buddhist philosophy, the two truths are two epistemological truths: two different ways to look at reality. The Sānlùn school (Chinese Mādhyamikas) thus rejected the ontological reading of the two truths. However, drawing on Buddha-nature thought, such as that of the Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra, and on Yogācāra sources, other Chinese Buddhist philosophers defended the view that the two truths did refer to two levels of reality (which were nevertheless non-dual and inferfused), one which was conventional, illusory and impermanent, and another which was eternal, unchanging and pure.[5]

Huayan school

[edit]The Huayan school or "Flower Garland" school is a tradition of Chinese Buddhist philosophy that flourished in medieval China during the Tang period (7th–10th centuries CE). It is based on the Avataṃsaka Sūtra, and on a lengthy Chinese interpretation of it, the Huayan Lun. The name "Flower Garland" is meant to suggest the crowning glory of profound understanding.

The most important philosophical contributions of the Huayan school were in the area of its metaphysics. It taught the doctrine of the mutual containment and interpenetration of all phenomena, as expressed in Indra's net. One thing contains all other existing things, and all existing things contain that one thing.

Distinctive features of this approach to Buddhist philosophy include:

- Truth (or reality) is understood as encompassing and interpenetrating falsehood (or illusion), and vice versa

- Good is understood as encompassing and interpenetrating evil

- Similarly, all mind-made distinctions are understood as "collapsing" in the enlightened understanding of emptiness (a tradition traced back to the Indian Buddhist philosopher Nāgārjuna)

Huayan teaches the Four Dharmadhātu, four ways to view reality:

- All dharmas are seen as particular separate events;

- All events are an expression of the absolute;

- Events and essence interpenetrate;

- All events interpenetrate.[44]

Absolute and relative in Zen Buddhism

[edit]

The teachings of Chán (Zen) Buddhism are expressed by a set of polarities: Buddha-nature (tathāgatagarbha), emptiness (śūnyatā),[45][46] absolute-relative,[47] sudden and gradual enlightenment (bodhi).[48]

The Prajnāpāramitā Sūtras and Mādhyamaka philosophy emphasized the non-duality of form and emptiness: "form is emptiness, emptiness is form", as it's written in the Heart Sutra.[47] The idea that the ultimate reality is present in the daily world of relative reality fitted into the Chinese culture, which emphasized the mundane world and society. But this does not tell how the absolute is present in the relative world. This question is answered in such schemata as the Verses of the Five Ranks of Tōzan[49] and the Oxherding Pictures.

Essence-function in Korean Buddhism

[edit]The polarity of absolute and relative is also expressed as "essence-function". The absolute is essence, the relative is function. They can't be seen as separate realities, but interpenetrate each other. The distinction does not "exclude any other frameworks such as neng-so or "subject-object" constructions", though the two "are completely different from each other in terms of their way of thinking".[50]

In Korean Buddhism, essence-function is also expressed as "body" and "the body's functions":

[A] more accurate definition (and the one the Korean populace is more familiar with) is "body" and "the body's functions". The implications of "essence/function" and "body/its functions" are similar, that is, both paradigms are used to point to a nondual relationship between the two concepts.[51]

A metaphor for essence-function is "A lamp and its light", a phrase from the Platform Sutra, where "essence" is the lamp and "function" its light.[52]

Tibetan Buddhism

[edit]Nyingma school

[edit]The Nyingma tradition is the oldest of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism.[2] It is founded on the first translations of Buddhist scriptures from Sanskrit into Tibetan (8th century CE). Tibetan Buddhist philosopher and polymath Mipham the Great (1846–1912) in his commentary to the Madhyamālaṃkāra of Śāntarakṣita (725–788) says:[53]

If one trains for a long time in the union of the two truths, the stage of acceptance (on the path of joining), which is attuned to primordial wisdom, will arise. By thus acquiring a certain conviction in that which surpasses intellectual knowledge, and by training in it, one will eventually actualize it. This is precisely how the Buddhas and the Bodhisattvas have said that liberation is to be gained.[54][note 6]

The following sentence from Mipham the Great's exegesis of Śāntarakṣita's Madhyamālaṃkāra highlights the relationship between the absence of the four extremes (mtha'-bzhi) and the non-dual or indivisible two truths (bden-pa dbyer-med):

The learned and accomplished [masters] of the Early Translations considered this simplicity beyond the four extremes, this abiding way in which the two truths are indivisible, as their own immaculate way.[55][note 7]

Understanding in other traditions

[edit]Jainism

[edit]The 2nd-century Digambara Jain monk and philosopher Kundakunda distinguishes between two perspectives of truth:

- Vyāvahāranaya or "mundane perspective".

- Niścayanaya or "ultimate perspective", also called "supreme" (pāramārtha) and "pure" (śuddha).[57]

For Kundakunda, the mundane realm of truth is also the relative perspective of normal folk, where the workings of karma operate and where things emerge, last for a certain time, and then perish. The ultimate perspective, meanwhile, is that of the liberated individual soul (jīvatman), which is "blissful, energetic, perceptive, and omniscient".[57]

Advaita Vedānta

[edit]The Advaita school of Vedānta philosophy took over from the Buddhist Mādhyamaka school the idea of levels of reality.[58] Usually two levels are being mentioned,[59] but the school's founder Ādi Śaṅkara uses sublation as the criterion to postulate an ontological hierarchy of three levels:[60][web 3][note 8]

- Pāramārthika: the absolute level, "which is absolutely real and into which both other reality levels can be resolved".[web 3] This experience can't be sublated by any other experience.[60]

- Vyāvahārika (or saṃvṛti-satya,[59] empirical or pragmatical): "our world of experience, the phenomenal world that we handle every day when we are awake".[web 3] It is the level in which both jīva (living creatures or individual souls) and Īśvara (Supreme Being) are true; here, the material world is also true.

- Prāthibhāsika (apparent reality or unreality): "reality based on imagination alone".[web 3] It is the level in which appearances are actually false, like the illusion of a snake over a rope, or a dream.

Mīmāṃsā

[edit]Chattopadhyaya notes that the 8th-century Mīmāṃsā philosopher Kumārila Bhaṭṭa rejected the two truths doctrine in his Shlokavartika.[62] Bhaṭṭa was highly influential with his defence of Vedic orthodoxy and rituals against the Buddhist rejection of Brahmanical beliefs and ritualism.[3] Some believe that his influence contributed to the decline of Buddhism in India,[63] since his lifetime coincides with the period in which Buddhism began to disappear from the Indian subcontinent.[64]

According to Kumārila, the two truths doctrine fundamentally is an idealist doctrine, which conceals the fact that "the theory of the nothingness of the objective world" is absurd:

[O]ne should admit that what does not exist, exists not; and what does exist, exists in the full sense. The latter alone is true, and the former false. But the idealist just cannot afford to do this. He is obliged instead to talk of 'two truths', senseless though this be.[62][note 9]

Correspondence with Pyrrhonism

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Pyrrhonism |

|---|

|

|

|

Thomas McEvilley notes a correspondence between Greek Pyrrhonism and the Buddhist Mādhyamaka school:

Sextus says [65] that there are two criteria:

- [T]hat by which we judge reality and unreality, and

- [T]hat which we use as a guide in everyday life.

According to the first criterion, nothing is either true or false[.] [I]nductive statements based on direct observation of phenomena may be treated as either true or false for the purpose of making everyday practical decisions.

The distinction, as Conze[66] has noted, is equivalent to the Madhyamaka distinction between "Absolute truth" (paramārthasatya), "the knowledge of the real as it is without any distortion,"[67] and "Truth so-called" (saṃvṛti satya), "truth as conventionally believed in common parlance.[67][68]

Thus in Pyrrhonism "absolute truth" corresponds to acatalepsy and "conventional truth" to phantasiai.

See also

[edit]- Index of Buddhism-related articles

- Nagarjuna

- Sacca

- Simran

- Tetralemma

- Upaya

- Secular Buddhism

- Double truth – View that religion and philosophy might arrive at contradictory truths

Notes

[edit]- ^ According to Lal Mani Joshi, Bhāviveka (6th century CE), the founder of the Svātantrika sub-school of Mādhyamaka philosophy, classified saṃvṛti into tathya-saṃvṛti and mithya-saṃvṛti.[20] Chandrakīrti (7th century CE), one of the main proponents of the Prasaṅgika sub-school of Mādhyamaka philosophy, divided saṃvṛti into loka-saṃvṛti and aloka-saṃvṛti.[20][21] Śāntideva (8th century CE) and his commentator Prajñakaramati (950-1030[web 2]) both use the terms tathya-saṃvṛti and mithya-saṃvṛti.[22][23] Kumārila Bhaṭṭa, an influential 8th-century Hindu philosopher of the Mīmāṃsā school, in commenting on Mādhyamaka philosophy, also uses the terms loka-saṃvṛti and aloka-saṃvṛti.[18] T. R. V. Murti, in his The Central Philosophy of Buddhism, uses the term aloka, and refers to the synonym mithya-saṃvṛti.[24]

Murti: "In calling it 'loka samvrti,' it is implied that there is some appearance which is aloka - non-empirical, i.e. false for the emprical consciousness even."[24]

David Seyfort Ruegg further comments: "The samvrti in worldly usage is termed lokasamvrti; and while it can serve no real purpose to distinguish an alokasamvrti opposed to it (from the point of view of ultimate reality both are unreal, though in different degrees from the relative standpoint), one may nevertheless speak of an alokasamvrti as distinct from it when considering that there exist persons who can be described as 'not of the world' (alokah) since they have experiences which are falsified because their sense-faculties are impaired (and which, therefore, do not belong to the general worldly consensus."[25] - ^ An often-used explanation in Madhyamaka literature is the perception of a snake. The perception of a real snake is tathya-saṃvṛti, concretely existing. In contrast, a rope which is mistakenly perceived as a snake is mithya-saṃvṛti. Ultimately both are false, but "the snake-seen-in-the-rope" is less true than the "snake-seen-in-the-snake". This gives an epistemological hierarchy in which tathya-saṃvṛti stands above mithya-saṃvṛti.[web 1][18] Another example given in the Mādhyamaka philosophical literature to distinguish between tathya-saṃvṛti and mithya-saṃvṛti is "water-seen-in-the-pool" (loka saṃvṛti) as contrasted with "water-seen-in-the-mirage" (aloka samvriti).

- ^ Mithya-saṃvṛti or "false saṃvṛti" cam also be given as asatya, "untruth."[web 1] Compare Peter Harvey, noting that in Chandogya Upanishad, 6.15.3 Brahman is satya, and Richard Gombrich, commenting on the Upanishadic identity of microcosm and macrocosm, c.q. Ātman and Brahman, which according to the Buddha is asat, "something that does not exist."[26] Compare also Atiśa: "One may wonder, "From where did all this come in the first place, and to where does it depart now?" Once examined in this way, [one sees that] it neither comes from anywhere nor departs to anywhere. All inner and outer phenomena are just like that."[27]

- ^ See also Susan Kahn, The Two Truths of Buddhism and The Emptiness of Emptiness

- ^ Some have interpreted paramarthika satya or "ultimate truth" as constituting a metaphysical 'Absolute' or noumenon, an "ineffable ultimate that transcends the capacities of discursive reason."[29] For example T. R. V. Murti (1955), The Central Philosophy of Buddhism, who gave a neo-Kantian interpretation.[30]

- ^ "Primordial wisdom" is a rendering of jñāna and "that which surpasses intellectual knowledge" may be understood as the direct perception (Sanskrit: pratyakṣa) of (dharmatā). "Conviction" may be understood as a gloss of faith (śraddhā). An effective analogue for "union", a rendering of the relationship held by the two truths, is interpenetration.

- ^ Blankleder and Fletcher of the Padmakara Translation Group give a somewhat different translation:

"The learned and accomplished masters of the Old Translation school take as their stainless view the freedom from all conceptual constructs of the four extremes, the ultimate reality of the two truths inseparably united."[56] - ^ According to Chattopadhyaya, the Advaitins retain the term pāramārtha-satya or pāramārthika-satya for the ultimate truth, and for the loka saṃvṛti of the Mādhyamikas they use the term vyāvahārika satya and for aloka saṃvṛti they use the term prāthibhāsika:[61]

- ^ Kumārila Bhaṭṭa: "The idealist talks of some 'apparent truth' or 'provisional truth of practical life', i.e. in his terminology, of samvriti satya. However, since in his own view, there is really no truth in this 'apparent truth', what is the sense of asking us to look at it as some special brand of truth as it were? If there is truth in it, why call it false at all? And, if it is really false, why call it a kind of truth? Truth and falsehood, being mutually exclusive, there cannot be any factor called 'truth' as belonging in common to both--no more than there can by any common factor called 'treeness' belonging to both the tree and the lion, which are mutually exclusive. On the idealist's own assumption, this 'apparent truth' is nothing but a synonym for the 'false'. Why, then, does he use this expression? Because it serves for him a very important purpose. It is the purpose of a verbal hoax. It means falsity, though with such a pedantic air about it as to suggest something apparently different, as it were. This is in fact a well known trick. Thus, to create a pedantic air, one can use the word vaktrasava [literally mouth-wine] instead of the simpler word lala, meaning saliva [vancanartha upanyaso lala-vaktrasavadivat]. But why is this pedantic air? Why, instead of simply talking of falsity, is the verbal hoax of an 'apparent truth' or samvriti? The purpose of conceiving this samvriti is only to conceal the absurdity of the theory of the nothingness of the objective world, so that it can somehow be explained why things are imagined as actually existing when they are not so. Instead of playing such verbal tricks, therefore, one should speak honestly. This means: one should admit that what does not exist, exists not; and what does exist, exists in the full sense. The latter alone is true, and the former false. But the idealist just cannot afford to do this. He is obliged instead to talk of 'two truths', senseless though this be."[62]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Matilal 2002, pp. 203–208.

- ^ a b c d e f Thakchoe, Sonam (Summer 2022). "The Theory of Two Truths in Tibet". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The Metaphysics Research Lab, Center for the Study of Language and Information, Stanford University. ISSN 1095-5054. OCLC 643092515. Archived from the original on 28 May 2022. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ a b Siderits, Mark (Spring 2015). "Buddha: Non-Self". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The Metaphysics Research Lab, Center for the Study of Language and Information, Stanford University. ISSN 1095-5054. OCLC 643092515. Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

The Buddha's "middle path" strategy can be seen as one of first arguing that there is nothing that the word "I" genuinely denotes, and then explaining that our erroneous sense of an "I" stems from our employment of the useful fiction represented by the concept of the person. While the second part of this strategy only receives its full articulation in the later development of the theory of two truths, the first part can be found in the Buddha's own teachings, in the form of several philosophical arguments for non-self. Best known among these is the argument from impermanence (S III.66–8) [...].

It is the fact that this argument does not contain a premise explicitly asserting that the five skandhas (classes of psychophysical element) are exhaustive of the constituents of persons, plus the fact that these are all said to be empirically observable, that leads some to claim that the Buddha did not intend to deny the existence of a self tout court. There is, however, evidence that the Buddha was generally hostile toward attempts to establish the existence of unobservable entities. In the Poṭṭhapāda Sutta (D I.178–203), for instance, the Buddha compares someone who posits an unseen seer in order to explain our introspective awareness of cognitions, to a man who has conceived a longing for the most beautiful woman in the world based solely on the thought that such a woman must surely exist. And in the Tevijja Sutta (D I.235–52), the Buddha rejects the claim of certain Brahmins to know the path to oneness with Brahman, on the grounds that no one has actually observed this Brahman. This makes more plausible the assumption that the argument has as an implicit premise the claim that there is no more to the person than the five skandhas. - ^ a b Lai 2003, p. 11.

- ^ a b Lai 2003.

- ^ Harvey 2012, p. 50.

- ^ a b c A. A. Macdonell, Sanskrit English Dictionary, Asian Educational Services, ISBN 978-8120617797, pp 330-331

- ^ yA Sanskrit English Dictionary

- ^ yam Monier Williams' Sanskrit English Dictionary, Univ of Koeln, Germany

- ^ Levinson, Jules (August 2006) Lotsawa Times Volume II Archived July 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Garfield 2002, p. 91.

- ^ a b Monier-Williams

- ^ McCagney: 82

- ^ Anguttara Nikaya I:60 (Jayatilleke: 361, in McCagney: 82)

- ^ PED

- ^ Khathāvatthu Aṭṭha kathǎ (Jayatilleke: 363, in McCagney: 84)

- ^ "Saṃvṛti-satya | Truth, Illusion & Reality | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2025-04-10.

- ^ a b c d Chattopadhyaya 2001, pp. 103–106.

- ^ "Paramārtha-satya | Buddhist concept | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2025-04-10.

- ^ a b c Joshi 1977, p. 174.

- ^ a b Nakamure 1980, p. 285.

- ^ a b c Dutt 1930.

- ^ a b c d Stcherbatsky 1989, p. 54.

- ^ a b Murti 2013, p. 245.

- ^ Seyfort Ruegg 1981, p. 74-75.

- ^ Gombrich 1990, p. 15.

- ^ Brunholzl 2004, p. 295.

- ^ a b Garfield 2002, p. 38–39.

- ^ a b c d Siderits 2003.

- ^ Westerhoff 2009, p. 9.

- ^ Nagarjuna, Mūlamadhyamakakārika 24:8–10. Jay L. Garfield|Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way: pp. 296, 298

- ^ Mūlamadhyamakakārikā Verse 24 Archived February 8, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Source: Kaccāyanagotta Sutta on Access to Insight (accessed: Sept 14th 2023)

- ^ Chattopadhyaya 2001, p. 21-3,94,104.

- ^ S.R. Bhatt & Anu Meherotra (1967). Buddhist Epistemology. p. 7.

- ^ Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya (2001). What is Living and What is Dead in Indian Philosophy 5th edition. p. 107.

- ^ Brown Holt 1995.

- ^ Goddard 2007, p. 10.

- ^ Verstappen 2004, p. 5.

- ^ Fowler 2005, p. 79.

- ^ a b Oh 2000.

- ^ Dumoulin 2005a, p. 45-49.

- ^ Lai 2003, p. 8.

- ^ Garfield & Edelglass 2011, p. 76.

- ^ Kasulis 2003, pp. 26–29.

- ^ McRae 2003, pp. 138–142.

- ^ a b Liang-Chieh 1986, p. 9.

- ^ McRae 2003, pp. 123–138.

- ^ Kasulis 2003, p. 29.

- ^ Park, Sung-bae (1983). Buddhist Faith and Sudden Enlightenment. SUNY series in religious studies. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-87395-673-7, ISBN 978-0-87395-673-4. Source: [1] (accessed: Friday April 9, 2010), p.147

- ^ Park, Sung-bae (2009). One Korean's approach to Buddhism: the mom/momjit paradigm. SUNY series in Korean studies: SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-7697-9, ISBN 978-0-7914-7697-0. Source: [2] (accessed: Saturday May 8, 2010), p.11

- ^ Lai, Whalen (1979). "Ch'an Metaphors: waves, water, mirror, lamp". Philosophy East & West; Vol. 29, no.3, July, 1979, pp.245–253. Source: [3] (accessed: Saturday May 8, 2010)

- ^ Commentary to the first couplet of quatrain/śloka 72 of the root text, (725–788) — Blumenthal, James (2008). "Śāntarakṣita", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2008 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.). Source: [4] (accessed: February 28, 2009), as rendered into English by the Padmakara Translation Group (2005: p. 304)

- ^ Śāntarakṣita (author); Mipham the Great (commentator); Padmakara Translation Group (2005). The Adornment of the Middle Way: Shantarakshita's Madhyamakalankara with commentary by Jamgön Mipham. Boston, Massachusetts, US: Shambhala Publications, Inc. ISBN 1-59030-241-9 (alk. paper), p. 304

- ^ Thomas, H. (trans.); Mipham the Great (author). Speech of Delight: Mipham's Commentary of Shantarakshita's Ornament of the Middle Way (2004). Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications. ISBN 1-55939-217-7, p. 127

- ^ Śāntarakṣita (author); Mipham the Great (commentator); Padmakara Translation Group (2005). The Adornment of the Middle Way: Shantarakshita's Madhyamakalankara with commentary by Jamgön Mipham. Boston, Massachusetts, US: Shambhala Publications, Inc. ISBN 1-59030-241-9 (alk. paper), p. 137

- ^ a b Long, Jeffery; Jainism: An Introduction, page 126.

- ^ Renard 2004, p. 130.

- ^ a b Renard 2004, p. 131.

- ^ a b Puligandla 1997, p. 232.

- ^ Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya (2001). What is Living and What is Dead in Indian Philosophy 5th edition. pp. 107, 104.

- ^ a b c Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya (2001). What is Living and What is Dead in Indian Philosophy 5th edition. pp. 370–1.

- ^ Sheridan 1995, p. 198-201.

- ^ Sharma 1980, p. 5-6.

- ^ Sextus Empericus, Outlines of Pyrrhonism, II.14–18; Anthologia Palatina (Palatine Anthology), VII. 29–35, and elsewhere

- ^ Conze 1959, pp. 140–141)

- ^ a b Conze (1959: p. 244)

- ^ McEvilley, Thomas (2002). The Shape of Ancient Thought. Allworth Communications. ISBN 1-58115-203-5., p. 474

Sources

[edit]Published sources

[edit]- Brown Holt, Linda (1995), "From India to China: Transformations in Buddhist Philosophy", Qi: The Journal of Traditional Eastern Health & Fitness

- Brunholzl, Karl (2004), Center of the Sunlit Sky, Snowlion

- Chattopadhyaya, Debiprasad (2001), What is Living and What is Dead in Indian Philosophy (5th ed.), People's Publishing House

- Conze, Edward (1959). Buddhism: Its Essence and Development. New York, US: Harper and Row.

- Dumoulin, Heinrich (2005a), Zen Buddhism: A History. Volume 1: India and China, World Wisdom Books, ISBN 978-0-941532-89-1

- Dutt, Nalinaksha (1930), "The Place of the Aryasatyas and Pratitya Sam Utpada in Hinayana and Mahayana", Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 6 (2): 101–127

- Fowler, Merv (2005), Zen Buddhism: Beliefs and Practices, Sussex Academic Press

- Garfield, Jay (2002), Empty Words: Buddhist Philosophy and Cross-cultural Interpretation, Oxford University Press

- Garfield, Jay L.; Priest, Graham (2003), "Nagarjuna and the Limits of Thought" (PDF), Philosophy East & West, 53 (1): 1–21, doi:10.1353/pew.2003.0004, hdl:11343/25880, S2CID 16724176

- Garfield, Jay L.; Edelglass, William (2011), The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy, Oup USA, ISBN 9780195328998

- Gethin, Rupert. Foundations of Buddhism. pp. 207, 235–245

- Goddard, Dwight (2007), History of Ch'an Buddhism previous to the times of Hui-neng (Wie-lang). In: A Buddhist Bible, Forgotten Books

- Gombrich, Richard (1990), "recovering the Buddha's Message" (PDF), in Ruegg, D.; Schmithausen, L. (eds.), Earliest Buddhism and Madhyamaka, BRILL[permanent dead link]

- Harvey, Peter (2012), An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices, Cambridge University Press

- Jayatilleke, K.N. Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge. George Allen and Unwin, 1963

- Joshi, Lal Mani (1977), Studies in the Buddhistic Culture of India During the Seventh and Eighth Centuries A.D., Motilal Banarsidass Publ.

- Kasulis, Thomas P. (2003), Ch'an Spirituality. In: Buddhist Spirituality. Later China, Korea, Japan and the Modern World; edited by Takeuchi Yoshinori, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Keown, Damien. Dictionary of Buddhism. Oxford University Press, 2003

- Liang-Chieh (1986), The Record of Tung-shan, William F. Powell (translator), Kuroda Institute

- Lai, Whalen (2003), Buddhism in China: A Historical Survey (PDF)

- Matilal, Bimal Krishna (2002). Ganeri, Jonardon (ed.). The Collected Essays of Bimal Krishna Matilal, Volume 1. New Delhi: Oxford University Press (2015 Reprint). ISBN 0-19-946094-9.

- Lopez, Donald S., "A Study of Svatantrika", Snow Lion Publications, 1987, pp. 192–217.

- McCagney, Nancy. The Philosophy of Openness. Rowman and Littlefield, 1997

- McRae, John (2003), Seeing Through Zen, The University Press Group Ltd, ISBN 9780520237988

- Monier-Williams, Monier; Leumann, Ernst; Cappeller, Carl (1899). A Sanskrit-English Dictionary, etymologically and philologically arranged with special reference to cognate Indo-European languages, Oxford: The Clarendon press

- Murti, T R V (2013). The Central Philosophy of Buddhism: A Study of the Madhyamika System. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-02946-3.

- Nakamure, Hajime (1980), Indian Buddhism: A Survey with Bibliographical Notes, Motilal Banarsidass Publ.

- Newland, Guy (1992). The Two Truths: in the Mādhyamika Philosophy of the Ge-luk-ba Order of Tibetan Buddhism. Ithaca, New York, US: Snow Lion Publications. ISBN 0-937938-79-3

- Oh, Kang-nam (2000), "The Taoist Influence on Hua-yen Buddhism: A Case of the Scinicization of Buddhism in China", Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal, 13

- Puligandla, Ramakrishna (1997), Fundamentals of Indian Philosophy, New Delhi: D.K. Printworld (P) Ltd.

- Renard, Gary (2004), The Disappearance of the Universe, Carlsbad, CA, US: Hay House

- Seyfort Ruegg, David (1981), The Literature of the Madhyamaka School of Philosophy in India, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag

- Sharma, Peri Sarveswara (1980), Anthology of Kumārilabhaṭṭa's Works, Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass

- Sheridan, Daniel P. (1995), "Kumarila Bhatta", in McGready, Ian (ed.), Great Thinkers of the Eastern World, New York: Harper Collins, ISBN 0-06-270085-5

- Siderits, Mark (2003), "On the Soteriological Significance of Emptiness", Contemporary Buddhism, 4 (1): 9–23, doi:10.1080/1463994032000140158, S2CID 144783831

- Stcherbatsky, Theodore (1989), Madhyamakakārikā, Motilal Banarsidass Publ.

- Suzuki, Daisetz Teitaro (1932), The Lankavatara Sutra, A Mahayana Text, Routledge Kegan Paul

- Verstappen, Stefan H. (2004), Blind Zen, Red Mansion Pub, ISBN 9781891688034

- Westerhoff, Jan (2009), Nagarjuna's Madhyamaka: A Philosophical Introduction, Oxford University Press

- Wilber, Ken (2000), Integral Psychology, Shambhala Publications

Web-sources

[edit]External links

[edit]![]() Works related to Saṃyukta Āgama 301: Kātyāyana Gotra Sūtra at Wikisource

Works related to Saṃyukta Āgama 301: Kātyāyana Gotra Sūtra at Wikisource