Scorpion Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scorpion

| Scorpions Temporal range: Early Silurian – present

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Hottentotta tamulus from Mangaon, Maharashtra, India | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Class: | Arachnida |

| Clade: | Arachnopulmonata |

| Order: | Scorpiones C. L. Koch, 1837 |

| Families | |

|

see Taxonomy | |

| |

| Native range of Scorpiones | |

Scorpions are predatory arachnids of the order Scorpiones. They have eight legs and are easily recognized by a pair of grasping pincers and a narrow, segmented tail, often carried in a characteristic forward curve over the back and always ending with a stinger. The evolutionary history of scorpions goes back 435 million years. They mainly live in deserts but have adapted to a wide range of environmental conditions, and can be found on all continents except Antarctica. There are over 2,500 described species, with 22 extant (living) families recognized to date. Their taxonomy is being revised to account for 21st-century genomic studies.

Scorpions primarily prey on insects and other invertebrates, but some species hunt vertebrates. They use their pincers to restrain and kill prey, or to prevent their own predation. The venomous sting is used for offense and defense. During courtship, the male and female grasp each other's pincers and dance while he tries to move her onto his sperm packet. All known species give live birth and the female cares for the young as their exoskeletons harden, transporting them on her back. The exoskeleton contains fluorescent chemicals and glows under ultraviolet light.

The vast majority of species do not seriously threaten humans, and healthy adults usually do not need medical treatment after a sting. About 25 species (fewer than one percent) have venom capable of killing a human, which happens frequently in the parts of the world where they live, primarily where access to medical treatment is unlikely.

Scorpions appear in art, folklore, mythology, and commercial brands. Scorpion motifs are woven into kilim carpets for protection from their sting. Scorpius is the name of a constellation; the corresponding astrological sign is Scorpio. A classical myth about Scorpius tells how the giant scorpion and its enemy Orion became constellations on opposite sides of the sky.

Etymology

[edit]The word scorpion originated in Middle English between 1175 and 1225 AD from Old French scorpion,[1] or from Italian scorpione, both derived from the Latin scorpio, equivalent to scorpius,[2] which is the romanization of the Greek σκορπίος – skorpíos,[3] with no native IE etymology (cfr. Arabic ʕaqrab 'scorpion', Proto-Germanic *krabbô 'crab').

Evolution

[edit]Fossil record

[edit]

Scorpion fossils have been found in many strata, including marine Silurian and estuarine Devonian deposits, coal deposits from the Carboniferous Period and in amber. Whether the early scorpions were marine or terrestrial has been debated, and while they had book lungs like modern terrestrial species,[4][5][6][7] the most basal such as Eramoscorpius were originally considered as still aquatic,[8] until it was found that Eramoscorpius had book lungs.[9] Over 100 fossil species of scorpion have been described.[10] The oldest found as of 2021 is Dolichophonus loudonensis, which lived during the Silurian, in present-day Scotland.[11] Gondwanascorpio from the Devonian is among the earliest-known terrestrial animals on the Gondwana supercontinent.[12] Some Palaeozoic scorpions possessed compound eyes similar to those of eurypterids.[13] The Triassic fossils Protochactas and Protobuthus belong to the modern clades Chactoidea and Buthoidea respectively, indicating that the crown group of modern scorpions had emerged by this time.[14]

Phylogeny

[edit]The Scorpiones are a clade within the pulmonate Arachnida (those with book lungs). Arachnida is placed within the Chelicerata, a subphylum of Arthropoda that contains sea spiders and horseshoe crabs, alongside terrestrial animals without book lungs such as ticks and harvestmen.[4] The extinct Eurypterida, sometimes called sea scorpions, though they were not all marine, are not scorpions; their grasping pincers were chelicerae, unlike those of scorpion which are second appendages.[15] Scorpiones is sister to the Tetrapulmonata, a terrestrial group of pulmonates containing the spiders and whip scorpions.[4]

Recent studies place pseudoscorpions as the sister group of scorpions in the clade Panscorpiones, which together with Tetrapulmonata makes up the clade Arachnopulmonata.[16]

Cladogram of current understanding of chelicerate relationships, after Sharma and Gavish-Regev (2025):[17]

| Chelicerata |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The internal phylogeny of the scorpions has been debated,[4] but genomic analysis consistently places the Bothriuridae as sister to a clade consisting of Scorpionoidea and Chactoidea. The scorpions diversified during the Devonian and into the early Carboniferous. The main division is into the clades Buthida and Iurida. The Bothriuridae diverged starting before temperate Gondwana broke up into separate land masses, completed by the Jurassic. The Iuroidea and Chactoidea are both seen not to be single clades, and are shown as "paraphyletic" (with quotation marks) in this 2018 cladogram.[18]

| Scorpiones |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Taxonomy

[edit]Carl Linnaeus described six species of scorpion in his genus Scorpio in 1758 and 1767; three of these are now considered valid and are called Scorpio maurus, Androctonus australis, and Euscorpius carpathicus; the other three are dubious names. He placed the scorpions among his "Insecta aptera" (wingless insects).[19] In 1801, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck divided up the "Insecta aptera", creating the taxon Arachnides for spiders, scorpions, and acari (mites and ticks), though it also contained the Thysanura, Myriapoda and parasites such as lice.[20] German arachnologist Carl Ludwig Koch created the order Scorpiones in 1837. He divided it into four families, the six-eyed scorpions "Scorpionides", the eight-eyed scorpions "Buthides", the ten-eyed scorpions "Centrurides", and the twelve-eyed scorpions "Androctonides".[21]

More recently, some twenty-two families containing over 2,500 species of scorpions have been described, with many additions and much reorganization of taxa in the 21st century.[22][4][23] There are over 100 described taxa of fossil scorpions.[10] This classification is based on Soleglad and Fet (2003),[24] which replaced Stockwell's older, unpublished classification.[25] Further taxonomic changes are from papers by Soleglad et al. (2005).[26][27]

The extant taxa to the rank of family (numbers of species in parentheses[22]) are:

- Order Scorpiones

- Parvorder Pseudochactida Soleglad & Fet, 2003

- Superfamily Pseudochactoidea Gromov, 1998

- Family Pseudochactidae Gromov, 1998 (1 sp.) (Central Asian scorpions of semi-savanna habitats)

- Superfamily Pseudochactoidea Gromov, 1998

- Parvorder Buthida Soleglad & Fet, 2003

- Superfamily Buthoidea C. L. Koch, 1837

- Family Buthidae C. L. Koch, 1837 (1209 spp.) (thick-tailed scorpions, including the most dangerous species)

- Family Microcharmidae Lourenço, 1996, 2019 (17 spp.) (African scorpions of humid forest leaf litter)

- Superfamily Buthoidea C. L. Koch, 1837

- Parvorder Chaerilida Soleglad & Fet, 2003

- Superfamily Chaeriloidea Pocock, 1893

- Family Chaerilidae Pocock, 1893 (51 spp.) (South and Southeast Asian scorpions of non-arid places)

- Superfamily Chaeriloidea Pocock, 1893

- Parvorder Iurida Soleglad & Fet, 2003

- Superfamily Chactoidea Pocock, 1893

- Family Akravidae Levy, 2007 (1 sp.) (cave-dwelling scorpions of Israel)

- Family Belisariidae Lourenço, 1998 (3 spp.) (cave-related scorpions of Southern Europe)

- Family Chactidae Pocock, 1893 (209 spp.) (New World scorpions, membership under revision)

- Family Euscorpiidae Laurie, 1896 (170 spp.) (harmless scorpions of the Americas, Eurasia, and North Africa)

- Family Superstitioniidae Stahnke, 1940 (1 sp.) (cave scorpions of Mexico and Southwestern United States)

- Family Troglotayosicidae Lourenço, 1998 (4 spp.) (cave-related scorpions of South America)

- Family Typhlochactidae Mitchell, 1971 (11 spp.) (cave-related scorpions of Eastern Mexico)

- Family Vaejovidae Thorell, 1876 (222 spp.) (New World scorpions)

- Superfamily Iuroidea Thorell, 1876

- Family Caraboctonidae Kraepelin, 1905 (23 spp.) (hairy scorpions)

- Family Hadruridae Stahnke, 1974 (9 spp.) (large North American scorpions)

- Family Iuridae Thorell, 1876 (21 spp.) (scorpions with a large tooth on inner side of moveable claw)

- Superfamily Scorpionoidea Latreille, 1802

- Family Bothriuridae Simon, 1880 (158 spp.) (Southern hemisphere tropical and temperate scorpions)

- Family Hemiscorpiidae Pocock, 1893 (16 spp.) (rock, creeping, or tree scorpions of the Middle East)

- Family Hormuridae Laurie, 1896 (92 spp.) (flattened, crevice-living scorpions of Southeast Asia and Australia)

- Family Rugodentidae Bastawade et al., 2005 (1 sp.) (burrowing scorpions of India)

- Family Scorpionidae Latreille, 1802 (183 spp.) (burrowing or pale-legged scorpions)

- Family Diplocentridae Karsch, 1880 (134 spp.) (closely related to and sometimes placed in Scorpionidae, but have spine on telson)

- Family Heteroscorpionidae Kraepelin, 1905 (6 spp.) (scorpions of Madagascar)

- Superfamily Chactoidea Pocock, 1893

Geographical distribution

[edit]Scorpions are found on all continents except Antarctica. They are usually among animal groups in that they are most diverse at the subtropics rather than the tropics, and are also less common near the poles.[28] New Zealand, and some of the islands in Oceania, have in the past had small populations of introduced scorpions, but they were exterminated.[29][28] Five colonies of Euscorpius flavicaudis have established themselves since the late 19th century in Sheerness in England at 51°N,[30][31][32] while Paruroctonus boreus lives as far north as Red Deer, Alberta.[33] A few species are on the IUCN Red List; Afrolychas braueri is classed as critically endangered (2012), Isometrus deharvengi as endangered (2016) and Chiromachus ochropus as vulnerable (2014).[34][35][36]

Scorpions are usually xerocoles, primarily living in deserts, but they can be found in virtually every terrestrial habitat including high-elevation mountains, caves, and intertidal zones. They are largely absent from boreal ecosystems such as the tundra, high-altitude taiga, and mountain tops.[37][4] The highest altitude reached by a scorpion is 5,500 meters (18,000 ft) in the Andes, for Orobothriurus crassimanus.[38] As regards microhabitats, scorpions may be ground-dwelling, tree-loving, rock-loving or sand-loving. Some species, such as Vaejovis janssi, are versatile and use any habitat on Socorro Island, Baja California, while others such as Euscorpius carpathicus, endemic to the littoral zone of rivers in Romania, occupy specialized niches.[39][40]

Morphology

[edit]

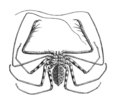

1 = Cephalothorax or prosoma;

2 = Preabdomen or mesosoma;

3 = Tail or metasoma;

4 = Claws or pedipalps;

5 = Legs;

6 = Mouth parts or chelicerae;

7 = Pincers or chelae;

8 = Moveable claw or tarsus;

9 = Fixed claw or manus;

10 = Stinger or aculeus;

11 = Telson (anus in previous joint);

12 = Opening of book lungs

Scorpions range in size from the 8.5 mm (0.33 in) Typhlochactas mitchelli of Typhlochactidae,[39] to the 23 cm (9.1 in) Heterometrus swammerdami of Scorpionidae.[41] The body of a scorpion is divided into two parts or tagmata: the cephalothorax or prosoma, and the abdomen or opisthosoma.[a] The opisthosoma consists of a broad anterior portion, the mesosoma or pre-abdomen, followed by a thinner tail-like posterior, the metasoma or post-abdomen.[43] External differences between the sexes are not obvious in most species. In some, the tail of the male is slenderer than that of the female.[44]

Cephalothorax

[edit]The cephalothorax comprises the carapace, eyes, chelicerae (mouth parts), pedipalps (which have chelae, commonly called claws or pincers) and four pairs of walking legs. Scorpions have two eyes on the top of the cephalothorax, and usually two to five pairs of eyes along the front corners of the cephalothorax. While unable to form sharp images, their central eyes are amongst the most light sensitive in the animal kingdom, especially in dim light, which makes it possible for nocturnal species to use starlight to navigate at night.[45] The chelicerae are at the front and below the carapace. They are pincer-like and have three segments and "teeth".[46][47] The brain of a scorpion is located in the front part of the cephalothorax, just above the esophagus.[48] As in other arachnids, the nervous system is highly concentrated in the cephalothorax, but has a long ventral nerve cord with segmented ganglia which may be a primitive trait.[49]

The pedipalp is a segmented, clawed appendage segmented into (from closest to the body outward) the coxa, trochanter, femur, patella, tibia (including the fixed claw and the manus) and tarsus (moveable claw).[50] Unlike those of some other arachnids, the eight-segmented legs have not been altered for other purposes, though they may occasionally be used for digging, and females may use them to catch emerging young. They are covered with many proprioceptors, bristles and sensory setae.[51] Depending on the species, the legs may have spines and spurs.[52]

Mesosoma

[edit]

The mesosoma or preabdomen is the broad part of the opisthosoma.[43] In the early stages of embryonic development the mesosoma consist of eight segments, but the first segment disappear before birth, so the mesosoma in scorpions actually consist of segments 2-8.[53][54][55] These anterior seven somites (segments) of the opisthosoma are each covered by a hardened plate, the tergite, on the back surface. Underneath, somites 3 to 7 are armored with matching plates called sternites. The underside of somite 1 has two covering over the genital opening. Sternite 2 forms the basal plate bearing the comb-like pectines,[56] which function as sensory organs.[57]

The next four somites, 3 to 6, all possess two spiracles each. They serve as openings for the scorpion's respiratory organs, known as book lungs, and vary in shape.[58][59] There are thus four pairs of book lungs; each consists of some 140 to 150 thin flaps or lamellae filled with air inside a pulmonary chamber, connected on the ventral side to an atrial chamber which opens into a spiracle. Bristles keep the lamellae from touching. A muscle opens the spiracle and widens the atrial chamber; dorsoventral muscles contract to constricts the pulmonary chamber, pushing air out, and relax to allow the chamber to refill.[60] The 7th and last somite lacks any notable structure.[58]

The mesosoma contains the heart or "dorsal vessel" which is the center of the scorpion's open circulatory system. The heart is continuous with a deep arterial system which spreads throughout the body. Sinuses return deoxygenated blood (hemolymph) to the heart; the blood is re-oxygenated by cardiac pores. The mesosoma also houses the reproductive system. The female gonads are three or four tubes which are aligned and have two to four transverse anastomoses connecting them. These tubes create oocytes and house developing embryos. They connect to two oviducts which connect to a single atrium leading to the genital orifice.[61] Males gonads are two pairs of cylindrical tubes with a ladder-like configuration; they contain spermatozoa-producing cysts. Both tubes end in a spermiduct, one on the opposite sides of the mesosoma. They connect to glandular symmetrical structures called paraxial organs, which end at the genital orifice. These create two halves of the chitin-based spermatophore which merge.[62][63]

Metasoma

[edit]

The "tail" or metasoma is divded into five segments and the telson, which is not strictly a segment. The five segments are merely body rings; they lack apparent sterna or terga, and are largest farthest from the center. These segments have keels, setae and bristles which may be used for taxonomic classification. The anus is at the back of the last segment, and is encircled by four anal papillae and the anal arch.[58] The tails of some species contain light receptors.[45]

The telson includes the vesicle, which contains a symmetrical pair of venom glands. Externally it bears the curved stinger, the hypodermic aculeus, equipped with sensory hairs. Venom ducts attached to the glands to transport the substance along the aculeus from the bulb of the gland to immediately near of the tip, where each of the paired ducts has its own venom pore.[64] An intrinsic muscle system attached to the glands pumps venom through the stinger into the intended victim.[65] The stinger contains metalloproteins with zinc, hardening the tip.[66] The optimal angle to launch a sting is around 30 degrees relative to the tip.[67]

Biology

[edit]

Scorpion are typically nocturnal or crepuscular, finding shelter during the day in burrows, cracks and bark.[68] Many species dig an elementary shelter underneath tiny stones. Scorpions may use burrows build by other animals or dig their own; scorpion burrows vary in complexity and depth. Hadrurus species dig burrows over 2 m (6 ft 7 in) deep while Urodacus hoplurus digs in spirals. Digging is done using the mouth parts, claws and legs. In several species, particularly of the family Buthidae, individuals can be found in the same shelter; bark scorpions may gather in groups of up to 30 individuals. In some species, families of females and young sometimes aggregate.[69]

Scorpions prefer areas where the temperature remains in the range of 11–40 °C (52–104 °F), but may survive temperatures from well below freezing to desert heat.[70][71] Scorpions can withstand intense heat: Leiurus quinquestriatus, Scorpio maurus and Hadrurus arizonensis can live in temperatures of 45–50 °C (113–122 °F) if they are sufficiently hydrated. Desert species must deal with the extreme changes in temperature from sunrise to sunset or between seasons; Pectinibuthus birulai lives in a temperature range of −30–50 °C (−22–122 °F). Scorpions that live outside deserts prefer lower temperatures. The ability to withstand the cold may be related to the increase in the sugar trehalose when the temperature drops. Some species hibernate.[72] Scorpions have immunity to ionizing radiation and have survived nuclear tests in Algeria[73] and Nevada.[74]

Desert scorpions have several adaptations for water conservation. They excrete insoluble compounds such as xanthine, guanine, and uric acid, not requiring water for their removal from the body. Guanine is the main component and maximizes the amount of nitrogen excreted. A scorpion's cuticle holds in moisture via lipids and waxes from epidermal glands, and protects against ultraviolet radiation. Even when dehydrated, a scorpion can tolerate high osmotic pressure in its blood.[75] Desert scorpions get most of their moisture from the food they eat but some can absorb water from the sand if it is humid enough. Species that live in denser vegetation and in more moderate temperatures will drink from puddles or water accumulated on plants.[76]

A scorpion uses its stinger both for killing prey and defense. Some species make direct, quick strikes with their tails while others make slower, more circular strikes which can more easily return the stinger to a position where it can strike again. Leiurus quinquestriatus can whip its tail at a speed of up to 128 cm/s (50 in/s) in a defensive strike.[77]

Mortality and defense

[edit]Scorpions may be attacked by other arthropods like ants, spiders, solifugids and centipedes. Major predators include frogs, lizards, snakes, birds, and mammals.[78] Predators adapted for hunting scorpions include the grasshopper mouse and desert long-eared bat, which are immune to their venom.[79][80] In one study, scorpion remains were found in 70% of the latter's droppings.[80] Scorpions host parasites including mites, scuttle flies, nematodes and some bacteria. The immune system of scorpions is strong enough to resist several types of bacterial infections.[81]

When threatened, a scorpion raises its claws and tail in a defensive posture. Some species stridulate to warn off predators by rubbing certain hairs, the stinger or the pectines.[82] Certain species have a preference for using either the claws or stinger as defense, depending on the size of the appendages.[83] A few scorpions, such as Parabuthus, Centruroides margaritatus, and Hadrurus arizonensis, squirt venom as 1 meter (3.3 ft) which can injure predators in the eyes.[84] Some Ananteris species can shed parts of their tail to escape predators. The parts do not grow back, leaving them unable to sting and defecate, but they can still kill small prey and reproduce for at least eight months afterward.[85]

Diet and feeding

[edit]

Scorpions generally prey on insects, particularly grasshoppers, crickets, termites, beetles and wasps. They also prey on spiders, solifugids, woodlice and even small vertebrates including lizards, snakes and mammals. Species with large claws may prey on earthworms and mollusks. The majority of species are opportunistic and consume a variety of prey though some may be highly specialized; Isometroides vescus specializes on certain burrowing spiders. Prey size depends on the size of the species. Several scorpion species are sit-and-wait predators, which involves a hungry scorpion staying at or near the entrance to their burrow until prey arrives. Others actively search for them. Scorpions detect their prey with mechanoreceptive and chemoreceptive hairs on their bodies and grab them with their claws. Small animals are merely killed with the claws, particularly by large-clawed species. Larger and more dangerous prey is given a sting.[86][87]

Scorpions, like other arachnids, digest their food externally. The chelicerae are used to rip small amounts of food off the prey item and into a pre-oral cavity underneath. The digestive juices from the gut are egested onto the food, and the digested food is then sucked into the gut. Any solid indigestible matter (such as exoskeleton fragments) is collected by setae in the pre-oral cavity and ejected. The sucked-in food is pumped into the midgut by the pharynx, where it is further digested. The waste is transported through the hindgut and out of the anus. Scorpions can eat large amounts of food during one meal. They can internally store food in a specialized organ and have a very low metabolic rate which enables some to survive up to a year without eating.[88]

Mating

[edit]

Most scorpions reproduce sexually, with male and female individuals; species in some genera, such as Hottentotta and Tityus, and the species Centruroides gracilis, Liocheles australasiae, and Ananteris coineaui have been reported, not necessarily reliably, to reproduce through parthenogenesis, in which unfertilized eggs develop into living embryos.[89] Receptive females produce pheromones which are picked up by wandering males using their pectines to comb the substrate. Males begin courtship by shifting their bodies back and forth, with the legs still, a behavior known as juddering. This appears to produce ground vibrations that are picked up by the female.[62]

The pair then make contact using their pedipalps, and perform a dance called the promenade à deux (French for "a walk for two"). In this dance, the male and female move around while facing each other, as the male searches for a suitable place to deposit his spermatophore. The courtship ritual can involve several other behaviors such as a cheliceral kiss, in which the male and female grasp each other's mouth-parts, arbre droit ("upright tree") where the partners elevate their posteriors and rub their tails together, and sexual stinging, in which the male stings the female to subdue her. The dance may be minutes to hours long.[90][91]

When the male has located a suitably stable surface, he deposits the spermatophore and guides the female over it. This allows the spermatophore to enter her genital opercula, which triggers release of the sperm, thus fertilizing the female. A mating plug then forms in the female to block further matings until she gives birth. The male and female then abruptly separate.[92][93] Sexual cannibalism after mating has only been reported anecdotally in scorpions.[94]

Birth and development

[edit]

Gestation in scorpions can last for over a year in some species.[95] They have two types of embryonic development; apoikogenic and katoikogenic. In the apoikogenic system, which is mainly found in the Buthidae, embryos develop in yolk-rich eggs inside follicles. The katoikogenic system is documented in Hemiscorpiidae, Scorpionidae and Diplocentridae, and involves the embryos growing in a diverticulum which has a teat-like structure for them to feed through.[96] Unlike the majority of arachnids, which are oviparous, hatching from eggs, scorpions seem to be universally viviparous, with live births; though apoikogenic species are ovoviviparous where young hatch from eggs inside the mother before being born.[97] They are unusual among terrestrial arthropods in the amount of care a female gives to her offspring.[98] The size of a brood varies by species, from 3 to over 100.[99] The body size of scorpions is not correlated either with brood size or with life cycle length.[100]

Before giving birth, the female raises the front of her body and positions her pedipalps and front legs under her for the young to fall through ("birth basket"). Each young exit through the genital opercula, expel the embryonic membrane, if any, and climb onto the mother's back where they remain until they have gone through at least one molt. The period before the first molt is called the pro-juvenile stage; the young lack the ability to eat or sting, but have suckers on their tarsi. This period lasts 5 to 25 days, depending on the species. The brood molt for the first time simultaneously in a process that lasts 6 to 8 hours, marking the beginning of the juvenile stage.[99]

Juvenile stages or instars generally resemble smaller versions of adults, with pincers, hairs and stingers. They are still soft and colorless, and thus continue to ride on their mother's back for protection. As days pass, they become harder and more pigmented. They may leave their mother temporarily, returning when they sense potential danger. When fully hardened, young can hunt and kill on their own and eventually become fully independent.[101] A scorpion goes through an average of six molts before maturing, which may not occur until it is 6 to 83 months old, depending on the species. They can reach an age of 25 years.[95]

Fluorescence

[edit]Scorpions glow a vibrant blue-green when exposed to certain wavelengths of ultraviolet light, such as that produced by a black light, due to fluorescent chemicals such as beta-carboline in the cuticle. Accordingly, a hand-held ultraviolet lamp has long been a standard tool for nocturnal field surveys of these animals. Fluorescence occurs as a result of sclerotization and increases in intensity with each successive instar.[102] This fluorescence may function in detecting light.[103]

Relationship with humans

[edit]Stings

[edit]

Scorpion venom serves to kill or paralyze prey rapidly, but only 25 species have venom that is deadly to humans, the most dangerous being Leiurus quinquestriatus.[39] People with allergies are especially at risk, but otherwise symptoms typically last no more than two days for non-deadly species.[104] Deaths from lethal stings are caused by excessive autonomic activity and toxic effects on cardiovascular or neuromuscular systems. Antivenom is used to counter scorpion envenomations, along with vasodilators to treat the cardiovascular system and benzodiazepines for the neuromuscular system. Severe hypersensitivity reactions including anaphylaxis to scorpion antivenin can occur, though rarely.[105]

Scorpion stings are a public health problem, particularly in the tropical and subtropical regions of the Americas, North Africa, the Middle East and India. Around 1.5 million scorpion envenomations occur each year, with around 2,600 deaths.[106][107][108] Mexico is one of the most affected countries, with the highest biodiversity of scorpions in the world, some 200,000 envenomations per year and at least 300 deaths.[109][110]

Efforts are made to prevent envenomation and to control scorpion populations. Prevention encompasses personal activities such as checking shoes and clothes before putting them on, not walking in bare feet or sandals, and filling in holes and cracks where scorpions might nest. Street lighting reduces scorpion activity. Control may involve the use of insecticides such as pyrethroids, or gathering scorpions manually with the help of ultraviolet lights. Domestic predators of scorpions, such as chickens and turkeys, can help to reduce the risk to a household.[106][107]

Potential medical use

[edit]

Scorpion venom is a mixture of neurotoxins; most of these are peptides, chains of amino acids.[112] Many of them interfere with membrane channels that transport sodium, potassium, calcium, or chloride ions. These channels are essential for nerve conduction, muscle contraction and many other biological processes. Some of these molecules may be useful in medical research and might lead to the development of new disease treatments. Among their potential therapeutic uses are as analgesic, anti-cancer, antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, antiparasitic, bradykinin-potentiating, and immunosuppressive drugs. As of 2020, no scorpion toxin-based drug is for sale, though chlorotoxin is being trialled for use against glioma, a brain cancer.[111]

Consumption

[edit]Scorpions are eaten in West Africa, Myanmar[113] and East Asia. Fried scorpion is traditionally eaten in Shandong, China.[114] There, scorpions can be cooked and eaten in a variety of ways, including roasting, frying, grilling, raw, or alive. The stingers are typically not removed, since heat negates the harmful effects of the venom.[115] In Thailand, scorpions are not eaten as often as other arthropods, such as grasshoppers, but they are sometimes fried as street food.[116] They are used in Vietnam to make snake wine (scorpion wine).[117]

Pets

[edit]Scorpions are often kept as pets. They are relatively simple to keep, the main requirements being a secure enclosure such as a glass terrarium with a lockable lid and the appropriate temperature and humidity for the chosen species, which typically means installing a heating mat and spraying regularly with a little water. The substrate needs to resemble that of the species' natural environment, such as peat for forest species, or lateritic sand for burrowing desert species. Scorpions in the genera Pandinus and Heterometrus are docile enough to handle. A large Pandinus may consume up to three crickets each week. Cannibalism is more common in captivity than in the wild and can be minimized by providing many small shelters within the enclosure and ensuring there is plenty of prey.[118][119] The pet trade has threatened wild populations of some scorpion species, particularly Androctonus australis and Pandinus imperator.[120]

Culture

[edit]-

Late period bronze figure of Isis-Serket

-

"Scorpion and snake fighting", Anglo-Saxon Herbal, c. 1050

-

The constellation Scorpius, depicted in Urania's Mirror as "Scorpio", London, c. 1825

-

A scorpion motif (two types shown) was often woven into Turkish kilim flatweave carpets, for protection from their sting.[121]

-

Scorpion pose in yoga has one or both legs pointing forward over the head, like a scorpion's tail.

The scorpion is a culturally significant animal. One of the earliest occurrences of the scorpion in culture is its inclusion, as Scorpio, in the 12 signs of the Zodiac by Babylonian astronomers during the Chaldean period.[122] In ancient Egypt, the goddess Serket, who protected the Pharaoh, was often depicted as a scorpion.[123] In Greek mythology, Artemis or Gaia sent a giant scorpion named Scorpius to kill the hunter Orion, who had said he would kill all the world's animals. Orion and the scorpion both became constellations; as enemies they were placed on opposite sides of the world, so when one rises in the sky, the other sets.[124][125][126]

Scorpions are mentioned in the Bible and the Talmud as symbols of danger and maliciousness.[125] The Sanskrit medical encyclopedia, The Suśrutasaṃhita, datable to before 500 CE, contains a detailed description of thirty types of scorpion, classified according to the levels of toxicity of their stings and their colours. Treatments for scorpion-sting are described.[127] Scorpions have also appeared as a motif in art, especially in Islamic art in the Middle East.[128] A scorpion motif is often woven into Turkish kilim flatweave carpets, for protection from their sting.[121] The scorpion is perceived both as an embodiment of evil and as a protective force such as a dervish's powers to combat evil.[128] In Muslim folklore, the scorpion portrays human sexuality.[128] Scorpions are used in folk medicine in South Asia, especially in antidotes for scorpion stings.[128]

The fable of The Scorpion and the Frog has been interpreted as showing that vicious people cannot resist hurting others, even when it is not in their interests.[129] More recently, the action in John Steinbeck's 1947 novella The Pearl centers on a poor pearl fisherman's attempts to save his infant son from a scorpion sting, only to lose him to human violence.[130] Scorpions have equally appeared in western artforms including film and poetry: the surrealist filmmaker Luis Buñuel made symbolic use of scorpions in his 1930 classic L'Age d'or (The Golden Age).[131]

Since classical times, the scorpion with its powerful stinger has been used to provide a name for weapons. In the Roman army, the scorpio was a torsion siege engine used to shoot a projectile.[132] The British Army's FV101 Scorpion was an armored reconnaissance vehicle or light tank in service from 1972 to 1994.[133] A version of the Matilda II tank, fitted with a flail to clear mines, was named the Matilda Scorpion.[134] Several ships of the Royal Navy and of the US Navy have been named Scorpion including an 18-gun sloop in 1803,[135] a turret ship in 1863,[136] a patrol yacht in 1898,[137] a destroyer in 1910,[138] and a nuclear submarine in 1960.[139]

The scorpion has served as the name or symbol of products and brands including Italy's Abarth racing cars[140] and a Montesa scrambler motorcycle.[141] A hand- or forearm-balancing asana in modern yoga as exercise with the back arched and one or both legs pointing forward over the head in the manner of the scorpion's tail is called Scorpion pose.[142][143]

Notes

[edit]- ^ As there is currently neither paleontological nor embryological evidence that arachnids ever had a separate thorax-like division, there exists an argument against the validity of the term cephalothorax, which means fused cephalon (head) and the thorax. Similarly, arguments can be formed against use of the term abdomen, as the opisthosoma of all scorpions contains a heart and book lungs, organs atypical of an abdomen.[42]

References

[edit]- ^ "Scorpion". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 5th Edition. 2016. Archived from the original on 22 November 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ "Scorpion". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 15 November 2015. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ σκορπίος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ a b c d e f Howard, Richard J.; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Legg, David A.; Pisani, Davide; Lozano-Fernandez, Jesus (2019). "Exploring the Evolution and Terrestrialization of Scorpions (Arachnida: Scorpiones) with Rocks and Clocks". Organisms Diversity & Evolution. 19 (1): 71–86. Bibcode:2019ODivE..19...71H. doi:10.1007/s13127-019-00390-7. hdl:10261/217081. ISSN 1439-6092.

- ^ Scholtz, Gerhard; Kamenz, Carsten (2006). "The Book Lungs of Scorpiones and Tetrapulmonata (Chelicerata, Arachnida): Evidence for Homology and a Single Terrestrialisation Event of a Common Arachnid Ancestor". Zoology. 109 (1): 2–13. Bibcode:2006Zool..109....2S. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2005.06.003. PMID 16386884.

- ^ Dunlop, Jason A.; Tetlie, O. Erik; Prendini, Lorenzo (2008). "Reinterpretation of the Silurian Scorpion Proscorpius osborni (Whitfield): Integrating Data from Palaeozoic and Recent Scorpions". Palaeontology. 51 (2): 303–320. Bibcode:2008Palgy..51..303D. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00749.x.

- ^ Kühl, G.; Bergmann, A.; Dunlop, J.; Garwood, R. J.; Rust, J. (2012). "Redescription and Palaeobiology of Palaeoscorpius devonicus Lehmann, 1944 from the Lower Devonian Hunsrück Slate of Germany". Palaeontology. 55 (4): 775–787. Bibcode:2012Palgy..55..775K. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2012.01152.x.

- ^ Waddington, Janet; Rudkin, David M.; Dunlop, Jason A. (January 2015). "A new mid-Silurian aquatic scorpion—one step closer to land?". Biology Letters. 11 (1): 20140815. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2014.0815. PMC 4321148. PMID 25589484.

- ^ Haug, C.; Wagner, P.; Haug, J.T. (31 December 2019). "The evolutionary history of body organisation in the lineage towards modern scorpions". Bulletin of Geosciences: 389–408. doi:10.3140/bull.geosci.1750. ISSN 1802-8225.

- ^ a b Dunlop, J. A.; Penney, D. (2012). Fossil Arachnids. Siri Scientific Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0956779540.

- ^ Anderson, Evan P.; Schiffbauer, James D.; Jacquet, Sarah M.; Lamsdell, James C.; Kluessendorf, Joanne; Mikulic, Donald G. (2021). "Stranger than a scorpion: a reassessment of Parioscorpio venator, a problematic arthropod from the Llandoverian Waukesha Lagerstätte". Palaeontology. 64 (3): 429–474. Bibcode:2021Palgy..64..429A. doi:10.1111/pala.12534. ISSN 1475-4983. S2CID 234812878. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ Gess, R. W. (2013). "The Earliest Record of Terrestrial Animals in Gondwana: a Scorpion from the Famennian (Late Devonian) Witpoort Formation of South Africa". African Invertebrates. 54 (2): 373–379. Bibcode:2013AfrIn..54..373G. doi:10.5733/afin.054.0206. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ Schoenemann, B.; Poschmann, M.; Clarkson ENK (2019). "Insights into the 400 million-year-old eyes of giant sea scorpions (Eurypterida) suggest the structure of Palaeozoic compound eyes". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 17797. Bibcode:2019NatSR...917797S. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53590-8. PMC 6882788. PMID 31780700.

- ^ Magnani, Fabio; Stockar, Rudolf; Lourenço, Wilson R. (2022). "Une nouvelle famille, genre et espèce de scorpion fossile du Calcaire de Meride (Trias Moyen) du Mont San Giorgio (Suisse)A new family, genus and species of fossil scorpion from the Meride Limestone (Middle Triassic) of Monte San Giorgio (Switzerland)". Faunitaxys. 10 (24). Lionel Delaunay: 1–7. doi:10.57800/FAUNITAXYS-10(24).

- ^ Waggoner, B. M. (12 October 1999). "Eurypterida: Morphology". University of California Museum of Paleontology Berkeley. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ Ontano, Andrew Z.; Gainett, Guilherme; Aharon, Shlomi; Ballesteros, Jesús A.; Benavides, Ligia R.; et al. (June 2021). "Taxonomic sampling and rare genomic changes overcome long-branch attraction in the phylogenetic placement of pseudoscorpions". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 38 (6): 2446–2467. doi:10.1093/molbev/msab038. PMC 8136511. PMID 33565584.

- ^ Sharma, Prashant P.; Gavish-Regev, Efrat (28 January 2025). "The Evolutionary Biology of Chelicerata". Annual Review of Entomology. 70 (1): 143–163. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-022024-011250. ISSN 0066-4170. PMID 39259983.

- ^ Sharma, Prashant P.; Baker, Caitlin M.; Cosgrove, Julia G.; Johnson, Joanne E.; Oberski, Jill T.; Raven, Robert J.; Harvey, Mark S.; Boyer, Sarah L.; Giribet, Gonzalo (2018). "A Revised Dated Phylogeny of Scorpions: Phylogenomic Support for Ancient Divergence of the Temperate Gondwanan Family Bothriuridae". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 122: 37–45. Bibcode:2018MolPE.122...37S. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2018.01.003. ISSN 1055-7903. PMID 29366829.

- ^ Fet, V.; Braunwalder, M. E.; Cameron, H. D. (2002). "Scorpions (Arachnida, Scorpiones) Described by Linnaeus" (PDF). Bulletin of the British Arachnological Society. 12 (4): 176–182. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ Burmeister, Carl Hermann C.; Shuckard, W. E. (trans) (1836). A Manual of Entomology. pp. 613ff. Archived from the original on 31 May 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ Koch, Carl Ludwig (1837). Übersicht des Arachnidensystems (in German). C. H. Zeh. pp. 86–92.

- ^ a b "The Scorpion Files". Jan Ove Rein. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ^ Kovařík, František (2009). "Illustrated Catalog of Scorpions, Part I" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 October 2010. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ^ Soleglad, Michael E.; Fet, Victor (2003). "High-level Systematics and Phylogeny of the Extant Scorpions (Scorpiones: Orthosterni)" (multiple parts). Euscorpius. 11: 1–175. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

- ^ Stockwell, Scott A. (1989). Revision of the Phylogeny and Higher Classification of Scorpions (Chelicerata) (PhD thesis). University of California, Berkeley.

- ^ Soleglad, Michael E.; Fet, Victor; Kovařík, F. (2005). "The Systematic Position of the Scorpion Genera Heteroscorpion Birula, 1903 and Urodacus Peters, 1861 (Scorpiones: Scorpionoidea)" (PDF). Euscorpius. 20: 1–38. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

- ^ Fet, Victor; Soleglad, Michael E. (2005). "Contributions to Scorpion Systematics. I. On Recent Changes in High-level Taxonomy" (PDF). Euscorpius (31): 1–13. ISSN 1536-9307. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 April 2018. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^ a b Polis 1990, p. 249.

- ^ "Critter of the Week The Pseudoscorpion!". RNZ. 6 April 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ^ Benton, T. G. (1992). "The Ecology of the Scorpion Euscorpius flavicaudis in England". Journal of Zoology. 226 (3): 351–368. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1992.tb07484.x.

- ^ Benton, T. G. (1991). "The Life History of Euscorpius flavicaudis (Scorpiones, Chactidae)" (PDF). The Journal of Arachnology. 19 (2): 105–110. JSTOR 3705658. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- ^ Rein, Jan Ove (2000). "Euscorpius flavicaudis". The Scorpion Files. Norwegian University of Science and Technology. Archived from the original on 26 April 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

- ^ Johnson, D. L. (2004). "The Northern Scorpion, Paruroctonus boreus, in Southern Alberta, 1983–2003". Arthropods of Canadian Grasslands 10 (PDF). Biological Survey of Canada. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 November 2015.

- ^ Gerlach, J. (2022) [errata version of 2022 assessment]. "Afrolychas braueri". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T21460801A211822304. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- ^ Deharveng, L.; Bedos, A. (2016). "Isometrus deharvengi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T89656504A89656508. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T89656504A89656508.en.

- ^ Gerlach, J. (2014). "Chiromachus ochropus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T196784A21568706. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T196784A21568706.en.

- ^ Polis 1990, pp. 251–253.

- ^ Stockmann & Ythier 2010, p. 151.

- ^ a b c Ramel, Gordon. "The Earthlife Web: The Scorpions". The Earthlife Web. Archived from the original on 9 October 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ^ Gherghel, I.; Sotek, A.; Papes, M.; Strugariu, A.; Fusu, L. (2016). "Ecology and Biogeography of the Endemic Scorpion Euscorpius carpathicus (Scorpiones: Euscorpiidae): a Multiscale Analysis". Journal of Arachnology. 44 (1): 88–91. doi:10.1636/P14-22.1. S2CID 87325752.

- ^ Rubio, Manny (2000). "Commonly Available Scorpions". Scorpions: Everything About Purchase, Care, Feeding, and Housing. Barron's. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-7641-1224-9.

The Guinness Book of Records claims [...] Heterometrus swammerdami, to be the largest scorpion in the world [9 inches (23 cm)]

- ^ Shultz, Stanley; Shultz, Marguerite (2009). The Tarantula Keeper's Guide. Barron's. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7641-3885-0.

- ^ a b Polis 1990, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Stockmann & Ythier 2010, p. 76.

- ^ a b Chakravarthy, Akshay Kumar; Sridhara, Shakunthala (2016). Arthropod Diversity and Conservation in the Tropics and Sub-tropics. Springer. p. 60. ISBN 978-981-10-1518-2. Archived from the original on 31 May 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ Polis 1990, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Stockmann 2015, p. 26.

- ^ Polis 1990, p. 38.

- ^ Polis 1990, p. 342.

- ^ Polis 1990, p. 12.

- ^ Polis 1990, p. 20.

- ^ Polis 1990, p. 74.

- ^ Farley, R. D. (2011). "The ultrastructure of book lung development in the bark scorpion Centruroides gracilis (Scorpiones: Buthidae) - PMC". Frontiers in Zoology. 8: 18. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-8-18. PMC 3199777. PMID 21791110.

- ^ "Chelicerata - Prashant P. Sharma" (PDF).

- ^ "Euscorpius - Marshall University" (PDF).

- ^ Polis 1990, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Knowlton, Elizabeth D.; Gaffin, Douglas D. (2011). "Functionally Redundant Peg Sensilla on the Scorpion Pecten". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 197 (9). Springer: 895–902. doi:10.1007/s00359-011-0650-9. ISSN 0340-7594. PMID 21647695. S2CID 22123929.

- ^ a b c Polis 1990, p. 15.

- ^ Wanninger, Andreas (2015). Evolutionary Developmental Biology of Invertebrates 3: Ecdysozoa I: Non-Tetraconata. Springer. p. 105. ISBN 978-3-7091-1865-8. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ Polis 1990, pp. 42–44.

- ^ Stockmann 2015, pp. 36, 45–46.

- ^ a b Stockmann 2015, p. 47.

- ^ Lautié, N.; Soranzo, L.; Lajarille, M.-E.; Stockmann, R. (2007). "Paraxial Organ of a Scorpion: Structural and Ultrastructural Studies of Euscorpius tergestinus Paraxial Organ (Scorpiones, Euscorpiidae)". Invertebrate Reproduction & Development. 51 (2): 77–90. doi:10.1080/07924259.2008.9652258. S2CID 84763256.

- ^ Yigit, N.; Benli, M. (2010). "Fine Structural Analysis of the Stinger in Venom Apparatus of the Scorpion Euscorpius mingrelicus (Scorpiones: Euscorpiidae)". Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins Including Tropical Diseases. 16 (1): 76–86. doi:10.1590/s1678-91992010005000003.

- ^ Stockmann 2015, p. 30.

- ^ Schofield, R. M. S. (2001). "Metals in cuticular structures". In Brownell, P. H.; Polis, G. A. (eds.). Scorpion Biology and Research. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 234–256. ISBN 978-0195084344.

- ^ van der Meijden, Arie; Kleinteich, Thomas (April 2017). "A biomechanical view on stinger diversity in scorpions". Journal of Anatomy. 230 (4): 497–509. doi:10.1111/joa.12582. PMC 5345679. PMID 28028798.

- ^ Stockmann 2015, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Stockmann & Ythier 2010, pp. 146, 152–154.

- ^ Hadley, Neil F. (1970). "Water Relations of the Desert Scorpion, Hadrurus arizonensis". Journal of Experimental Biology. 53 (3): 547–558. Bibcode:1970JExpB..53..547H. doi:10.1242/jeb.53.3.547. PMID 5487163. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 April 2008. Retrieved 30 December 2006.

- ^ Hoshino, K.; Moura, A. T. V.; De Paula, H. M. G. (2006). "Selection of Environmental Temperature by the Yellow Scorpion Tityus serrulatus Lutz & Mello, 1922 (Scorpiones, Buthidae)". Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins Including Tropical Diseases. 12 (1): 59–66. doi:10.1590/S1678-91992006000100005. hdl:11449/68851.

- ^ Stockmann 2015, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Stockmann & Ythier 2010, p. 157.

- ^ Allred, Dorald M. (1973). "Effects of a Nuclear Detonation on Arthropods at the Nevada Test Site". Brigham Young University Science Bulletin. 18 (4): 1–20 – via BYU SchoalarsArchive.

- ^ Cowles, Jillian (2018). Amazing Arachnids. Princeton University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-691-17658-1.

- ^ Stockmann & Ythier 2010, p. 156.

- ^ Coelho, P.; Kaliontzopoulou, A.; Rasko, M.; van der Meijden, A. (2017). "A 'Striking' Relationship: Scorpion Defensive Behaviour and its Relation to Morphology and Performance". Functional Ecology. 31 (7): 1390–1404. Bibcode:2017FuEco..31.1390C. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.12855.

- ^ Stockmann 2015, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Thompson, Benjamin (June 2018). "The Grasshopper Mouse and Bark Scorpion: Evolutionary Biology Meets Pain Modulation and Selective Receptor Inactivation". The Journal of Undergraduate Neuroscience Education. 16 (2): R51 – R53. PMC 6057761. PMID 30057511.

- ^ a b Holderied, M.; Korine, C.; Moritz, T. (2010). "Hemprich's Long-eared Bat (Otonycteris hemprichii) as a Predator of Scorpions: Whispering Echolocation, Passive Gleaning and Prey Selection". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 197 (5): 425–433. doi:10.1007/s00359-010-0608-3. PMID 21086132. S2CID 25692517.

- ^ Stockmann 2015, pp. 38, 45.

- ^ Stockmann 2015, p. 37.

- ^ van der Meijden, A.; Coelho, P. L.; Sousa, P.; Herrel, A. (2013). "Choose your Weapon: Defensive Behavior is Associated with Morphology and Performance in Scorpions". PLOS ONE. 8 (11): e78955. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...878955V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078955. PMC 3827323. PMID 24236075.

- ^ Stockmann & Ythier 2010, p. 90.

- ^ Mattoni, C. I.; García-Hernández, S.; Botero-Trujillo, R.; Ochoa, J. A.; Ojanguren-Affilastro, A. A.; Pinto-da-Rocha, R.; Prendini, L. (2015). "Scorpion Sheds 'Tail' to Escape: Consequences and Implications of Autotomy in Scorpions (Buthidae: Ananteris)". PLOS ONE. 10 (1): e0116639. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1016639M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0116639. PMC 4309614. PMID 25629529. S2CID 17870490.

- ^ Stockmann 2015, pp. 32–38.

- ^ Murray, Melissa (3 December 2020). "Scorpions". Australian Museum. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ Polis 1990, pp. 296–298.

- ^ Lourenço, Wilson R. (2008). "Parthenogenesis in Scorpions: Some History – New Data". Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins Including Tropical Diseases. 14 (1). doi:10.1590/S1678-91992008000100003. ISSN 1678-9199.

- ^ Stockmann 2015, pp. 47–50.

- ^ Stockmann & Ythier 2010, pp. 126–128.

- ^ Stockmann 2015, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Stockmann & Ythier 2010, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Peretti, A. (1999). "Sexual Cannibalism in Scorpions: Fact or Fiction?". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 68 (4): 485–496. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1999.tb01184.x. ISSN 0024-4066.

- ^ a b Polis 1990, p. 161.

- ^ Warburg, M. R. (2010). "Reproductive System of Female Scorpion: A Partial Review". The Anatomical Record. 293 (10): 1738–1754. doi:10.1002/ar.21219. PMID 20687160. S2CID 25391120.

- ^ Warburg, Michael R. (5 April 2012). "Pre- and Post-parturial Aspects of Scorpion Reproduction: a Review". European Journal of Entomology. 109 (2): 139–146. doi:10.14411/eje.2012.018.

- ^ Polis 1990, p. 6.

- ^ a b Lourenço, Wilson R. (2000). "Reproduction in Scorpions, with Special Reference to Parthenogenesis" (PDF). In Toft, S.; Scharff, N. (eds.). European Arachnology. Aarhus University Press. pp. 74–76. ISBN 978-877934-0015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 May 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Monge-Nájera, J. (2019). "Scorpion Body Size, Litter Characteristics, and Duration of the Life Cycle (Scorpiones)". Cuadernos de Investigación UNED. 11 (2): 101–104.

- ^ Stockmann 2015, p. 54.

- ^ Stachel, Shawn J.; Stockwell, Scott A.; Van Vranken, David L. (August 1999). "The Fluorescence of Scorpions and Cataractogenesis". Chemistry & Biology. 6 (8): 531–539. doi:10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80085-4. PMID 10421760.

- ^ Gaffinr, Douglas D.; Bumm, Lloyd A.; Taylor, Matthew S.; Popokina, Nataliya V.; Mann, Shivani (2012). "Scorpion Fluorescence and Reaction to Light". Animal Behaviour. 83 (2): 429–436. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2011.11.014. S2CID 17041988. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Insects and Scorpions". NIOSH. 1 July 2016. Archived from the original on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ Bhoite, R. R.; Bhoite, G. R.; Bagdure, D. N.; Bawaskar, H. S. (2015). "Anaphylaxis to Scorpion Antivenin and its Management Following Envenomation by Indian Red Scorpion, Mesobuthus tamulus". Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine. 19 (9): 547–549. doi:10.4103/0972-5229.164807. PMC 4578200. PMID 26430342.

- ^ a b Feola, A.; Perrone, M. A.; Piscopo, A.; Casella, F.; Della Pietra, B.; Di Mizio, G. (2020). "Autopsy Findings in Case of Fatal Scorpion Sting: A Systematic Review of the Literature". Healthcare. 8 (3): 325. doi:10.3390/healthcare8030325. PMC 7551928. PMID 32899951.

- ^ a b Stockmann & Ythier 2010, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Santos, Maria S.V.; Silva, Cláudio G.L.; Neto, Basílio Silva; Grangeiro Júnior, Cícero R.P.; Lopes, Victor H.G.; Teixeira Júnior, Antônio G.; Bezerra, Deryk A.; Luna, João V.C.P.; Cordeiro, Josué B.; Júnior, Jucier Gonçalves; Lima, Marcos A.P. (2016). "Clinical and Epidemiological Aspects of Scorpionism in the World: A Systematic Review". Wilderness & Environmental Medicine. 27 (4): 504–518. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2016.08.003. ISSN 1080-6032. PMID 27912864. Archived from the original on 31 May 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ Dehesa-Dávila, Manuel; Possani, Lourival D. (1994). "Scorpionism and Serotherapy in Mexico". Toxicon. 32 (9): 1015–1018. Bibcode:1994Txcn...32.1015D. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(94)90383-2. ISSN 0041-0101. PMID 7801335.

- ^ Santibáñez-López, Carlos; Francke, Oscar; Ureta, Carolina; Possani, Lourival (2015). "Scorpions from Mexico: From Species Diversity to Venom Complexity". Toxins. 8 (1): 2. doi:10.3390/toxins8010002. ISSN 2072-6651. PMC 4728524. PMID 26712787.

- ^ a b Ahmadi, Shirin; Knerr, Julius M.; Argemi, Lídia; Bordon, Karla C. F.; Pucca, Manuela B.; Cerni, Felipe A.; Arantes, Eliane C.; Çalışkan, Figen; Laustsen, Andreas H. (12 May 2020). "Scorpion Venom: Detriments and Benefits". Biomedicines. 8 (5). MDPI AG: 118. doi:10.3390/biomedicines8050118. ISSN 2227-9059. PMC 7277529. PMID 32408604.

- ^ Rodríguez de la Vega, Ricardo C.; Vidal, Nicolas; Possani, Lourival D. (2013). "Scorpion Peptides". In Kastin, Abba J. (ed.). Handbook of Biologically Active Peptides (2nd ed.). Academic Press. pp. 423–429. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-385095-9.00059-2. ISBN 978-0-12-385095-9.

- ^ Stockmann & Ythier 2010, p. 147.

- ^ Forney, Matthew (11 June 2008). "Scorpions for Breakfast and Snails for Dinner". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ Albers, Susan (15 May 2014). "How to Mindfully Eat a Scorpion". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ Fernquest, Jon (30 March 2016). "Fried Scorpion Anyone?". Bangkok Post. Archived from the original on 31 May 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ Lachenmeier, Dirk W.; Anh, Pham Thi Hoang; Popova, Svetlana; Rehm, Jürgen (11 August 2009). "The Quality of Alcohol Products in Vietnam and Its Implications for Public Health". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 6 (8): 2090–2101. doi:10.3390/ijerph6082090. PMC 2738875. PMID 19742208.

- ^ "Scorpion Caresheet". Amateur Entomologists' Society. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ Stockmann & Ythier 2010, pp. 144, 173–177.

- ^ Pryke 2016, pp. 187–189.

- ^ a b Erbek, Güran (1998). Kilim Catalogue No. 1 (1st ed.). May Selçuk A. S. "Motifs", before page 1.

- ^ Polis 1990, p. 462.

- ^ "Serqet". British Museum. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ Kerényi, C. (1974). "Stories of Orion". The Gods of the Greens. Thames and Hudson. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-500-27048-6.

- ^ a b Stockmann & Ythier 2010, p. 179.

- ^ Pryke 2016, pp. 126–129.

- ^ Sharma, Priya Vrat (2001). Suśruta-Saṃhitā with English Translation of Text and Ḍalhaṇa's Commentary Along With Critical Notes. Vol. 3. Varanasi: Chaukhambha Visvabharati. pp. 87–91.

- ^ a b c d Frembgen, Jürgen Wasim (2004). "The Scorpion in Muslim Folklore". Asian Folklore Studies. 63 (1): 95–123. Archived from the original on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ Takeda, A. (2011). "Blumenreiche Handelswege: Ost-westliche Streifzüge auf den Spuren der Fabel Der Skorpion und der Frosch" [Flowery Trade Routes: East-Western forays into the footsteps of the fable The Scorpion and the Frog] (PDF). Deutsche Vierteljahrsschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Geistesgeschichte (in German). 85 (1): 124–152. doi:10.1007/BF03374756. S2CID 170169337. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 November 2020. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

(German) Die Moral der Fabel besagt: Manche Menschen handeln von Natur aus mörderisch und selbst-mörderisch zugleich. (English) The moral of the fable says: Some people act naturally murderous and self-murderous at the same time.

- ^ Meyer, Michael (2005). "Diamond in the Rough: Steinbeck's Multifaceted Pearl". The Steinbeck Review. 2 (2 (Fall 2005)): 42–56. JSTOR 41581982.

- ^ Weiss, Allen S. (1996). "Between the sign of the scorpion and the sign of the cross: L'Age d'or". In Kuenzli, Rudolf E. (ed.). Dada and Surrealist Film. MIT Press. pp. 159. ISBN 978-0-262-61121-3.

- ^ Vitruvius, De Architectura, X:10:1–6.

- ^ "Scorpion". Jane's Information Group. Archived from the original on 21 February 2008. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ Fletcher, David (2017). British Battle Tanks: British-made Tanks of World War II. Bloomsbury. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-4728-2003-7. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth. p. 291. ISBN 978-1-86176-246-7.

- ^ Parkes, Oscar (1990). British Battleships (reprint of the 1957 ed.). Naval Institute Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

- ^ "[untitled]". Marine Review. 14 (11). Cleveland, Ohio: 1. 10 September 1896.

- ^ "[untitled]". Naval and Military Intelligence. The Times. London. 31 August 1910. p. 5. Archived from the original on 31 May 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ "USS Scorpion (SSN 589) May 27, 1968 – 99 Men Lost". United States Navy. 2007. Archived from the original on 12 March 2008. Retrieved 9 April 2008.

- ^ "The History of Abarth's Logo". Museo del marchio italiano. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

The company logo has been the scorpion since the very start; Carlo Abarth did not only want it as a reference to his zodiac sign, but also because it was an original and hard to imitate logo. At the beginning the scorpion was free from any contour and featured the typo "Abarth & Co.- Torino". In 1954 a shield was added, as symbol of victory and passion;

- ^ Salvadori, Clement (17 January 2019). "Retrospective: 1974–1977 Montesa Cota 247-T". Rider Magazine. Archived from the original on 27 June 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

Permanyer persisted, built larger engines, and in 1965 showed the 247cc engine (21 horsepower at 7,000 rpm) in a Scorpion motocrosser.

- ^ Anon; Budig, Kathryn (1 October 2012). "Kathryn Budig Challenge Pose: Scorpion in Forearm Balance". Yoga Journal. Archived from the original on 27 June 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ Iyengar, B. K. S. (1991). Light on Yoga. Thorsons. pp. 386–388. ISBN 978-0-00-714516-4. OCLC 51315708.

Further reading

[edit]- Polis, Gary (1990). The Biology of Scorpions. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1249-1. OCLC 18991506.

- Pryke, L. M. (2016). Scorpion. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1780236254.

- Stockmann, Roland; Ythier, Eric (2010). Scorpions of the World. N. A. P. Editions. ISBN 978-2913688117.

- Stockmann, Roland (2015). "Introduction to Scorpion Biology and Ecology". In Gopalakrishnakone, P.; Possani, L.; F. Schwartz, E.; Rodríguez de la Vega, R. (eds.). Scorpion Venoms. Springer. pp. 25–59. ISBN 978-94-007-6403-3.

External links

[edit]- American Museum of Natural History - Scorpion Systematics Research Group

- CDC – Insects and Scorpions – NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic

![A scorpion motif (two types shown) was often woven into Turkish kilim flatweave carpets, for protection from their sting.[121]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2a/Scorpion_kilim_motif.jpg/250px-Scorpion_kilim_motif.jpg)